Credit Copilot

Introduction

"Every year we approve a capital works program for projects that we believe the community wants us to do. After long discussions and deliberation, which can be acrimonious, we finally agree to fund a program and then it is not delivered. It is frustrating and lets everyone down, especially those people in the community who are waiting for projects to be completed."

Anonymous councillor.

I have heard this, or a variation of it, said many times by councillors. They are rightly frustrated that a difficult and politically fraught decision they make ends up not being implemented. The CEO is often equally as frustrated because they have been asked to do something that is beyond the capabilities of their organisation. It is a situation that has existed for some time and, as I will show you, seems to have become worse in recent years.

This was the situation when I started looking for the root causes of difficulties in setting a deliverable capital works program. It is where this story begins.

Do we know what the problem is with capital works delivery?

The simple answer to this question is no. The are no councils consistently delivering all of the approved capital works program and many don't reach the target of spending 80% or more of the program budget. Few councils understand their capital works delivery as a flow and many have tried to improve delivery performance by creating specialised and centralised departments (e.g. an Enterprise Project Management Office) to take the responsibility for the capital program. This hasn't always worked.

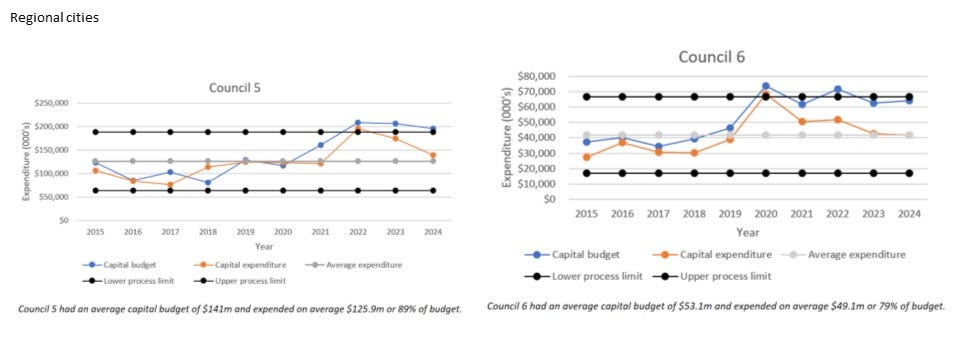

To start my story and to illustrate the challenge, I have put together charts showing capital works program delivery performance of a sample of councils between 2015 and 2024. Local government is a diverse sector, so I have picked 2 councils at random from each of the groupings typically used for sector analysis - metropolitan councils, interface councils, regional cities, large shires, and small shires. In the end I looked at 10 councils out of the 79 councils in Victoria.

In the charts, the blue line shows the target expenditure set when the council has approved the capital works budget and the orange line shows actual expenditure achieved. This shows what the councils set out to do and then what they actually did.

I have added black lines to show upper and lower limits of each councils capability to deliver capital works delivery. I won't go in to a complicated explanation of how they have been calculated except to say it is based on the work of W. Edwards Deming and calculated using the average moving range of the annual capital expenditure multiplied by a scaling factor of 2.66. The product is then either added to the average to calculate the upper limit, or subtracted from the average to give the lower limit. This shows what each council's capital works delivery system is capable of producing.

These charts give some critical insights into what is happening. The first is the budgets that have been set are frequently outside the capability of the system and, therefore, are unachievable. The objective set by the council cannot be achieved without risking damage to the delivery system. The second is the variability in actual performance. Any result falling between the upper and lower limits can be expected but the variability is often significant.

Any result falling outside the limits may be the result of a special cause from outside the capital works delivery system. It is interesting to note the impact of Covid (2020 to 2021) on performance and what appears to be an attempt to catch up afterwards by councils setting targets that their delivery system was incapable of achieving.

It is worth noting that the capability being analysed is simply spending money. Whether the money has been spent on the projects it was intended to be spent on, or whether spending 80% of the money means delivery of 80% of the approved capital works program is unknown.

What the charts do show that there is a mismatch between the capability of council systems to deliver capital works and the expectations of the councillors when approving a capital works program.

Political and managerial accountability

Tension exists between the Council with its political accountability to constituents in the community who will vote at the next election (when councillors will need to justify the decisions they have made), and the CEO who has managerial accountability to use their authority to do what the Council has directed. They will need to justify the decisions they have made when their remuneration is reviewed or their contract is up for renewal.

These competing accountabilities lie at the heart of the difficulty of approving a carefully prioritised and achievable annual capital works program.

The firm commitments required by the CEO to be able to do their job and be held accountable for what they achieve, conflict with the flexible commitments that councillors want to make so that everyone thinks they are getting what they want. They may in fact go further and want to promise that everyone will get what they want, especially in the lead up to an election.

An experienced former council CEO wrote a highly informative thesis on performance measurement in 1999, in which he explored the differences between political and managerial accountability, and how this affects agreement between the elected representatives and the CEO on council goals and policy. He pointed out that it is not always in the interests of councillors to identify clear and achievable objectives, especially when resources are scarce because some community interest groups will miss out. As a result they approve unachievable capital programs. In comparison, the CEO wants to optimise the use of available financial resources and be measured against defined objectives. They need the capital program to be both affordable and achievable within the capability of the organisation.

There are some fundamental conflicts - political and managerial accountability for the projects selected, and for approving an affordable and deliverable capital works program.

How is a capital allocation policy useful?

The starting point for a deliverable capital works program is consistent decision making to give certainty about the future. Future capital works budgets, and the types of projects to be included in them, must be predictable if the organisation is to develop an effective delivery system. Predictability is the precondition necessary to develop capability and where councils have these conditions the results are evident.

For example, here is another metropolitan council's results between 2015 and 2024.

This council had an average budget of $76.2 and expended on average $53m or 70% of budget. Whilst this council didn't reach the target of 80% expenditure of capital program budget, it did consistently deliver over $40m. In the 10 year period it increased its capability from $40m to $60m, and may have done much better without the impact of Covid, as the red 'line of best fit' shows. This council has consistently spent over 140% of its depreciation on asset renewal and averages 94% expenditure of the renewal capital allocation, which happens to also be about 50% of the total capital budget. There is certainty that enables future planning and building capability.

Councillors do spend a considerable amount of time deliberating on capital works projects when approving the budget. They spend much more time than they do in approving the operating budget and go into much more detail because the Local Government Act entitles them to approve each and every project in the capital budget, unlike the operating budget where they are asked to approve broad categories of expenditure on wages, materials and contractors. This difference in the level of councillor involvement in decision making creates another fundamental conflict when the funding of services in the operating budget creates demand for capital assets that is unknown to councillors and, as a result, is unmet in the approved capital works budget.

Approved capital works programs do not always contain projects that optimise use of available funds in meeting current priorities. This became evident when I started looking at what was actually happening with the approval of capital works programs.

How was the capital allocation policy created?

To begin, I started looking at what had happened with capital works delivery in previous years and why the program hadn't been delivered. I started looking for systemic factors likely to be affecting the organisational capability to deliver its approved capital works program. The starting point was analysis of historical expenditure in approved capital works programs. I wanted to understand what projects the Council had decided to spend its money on.

Project typology

What became apparent was that there are categories of projects that are typically funded every year in the capital works program, and each year there was a similar amount of funding allocated to each category. In addition, some types of projects were not receiving the amount of funding that Council adopted strategies and plans suggested they should. A typology of 5 capital project categories emerged.

The first category of projects identified was asset renewal or replacement. The Victorian Auditor General (VAGO) advises that councils should allocate an amount of capital equal for asset renewal or replacement that is at least 50% of the annual depreciation. As we have seen, some councils allocate much more. Depreciation is intended to reflect the rate at which assets are consumed through use. Most council try to allocate capital equal to 50% of depreciation for renewal unless they have a reasons to allocate more or less. This is the category of projects that is potentially easiest to deliver if it is able to be planned in advance. Hence the success of Council 11.

The second category was asset upgrading, expansion or the creation of new assets in response to changing or increasing demand for services. There are no guidelines on how much a council should spend on improving or creating assets, except most councils accept that looking after existing assets should take precedence over making new ones.

The third category was meeting external commitments. In this case it was Developer Contribution Plans (DCPs) but there are other types of commitments councils make that must be funded. For example, they may enter into contracts of sale to acquire assets over several financial years. In the case of DCPs, they are long-term commitments with considerable risk and the council has limited control over when the funding to meet those commitments will be required. An 'average' amount of funding required each year can be estimated as a starting point from the DCPs. There can also be a need for additional Council funds to upgrade assets if the community needs and expectations have changed in the time since the DCP was agreed.

The fourth category was investment in the council organisation. This included projects to improve council offices used by staff; replace furniture; buy cars and other equipment staff need; provide new or upgraded computers and software; and invest in energy efficient equipment to reduce future energy costs. Today, many of these expenditures are no longer regarded as capital because they were below capitalisation thresholds or they are now purchased through operating leases or monthly payments for consumption (e.g. cars and IT applications). Nonetheless, business cases found their way into the capital program because there was no other funding source available.

The last category of capital expenditure was 'strategic' projects. It mainly included opportunistic capital expenditure that the Council decided were required to achieve its short or long-term strategic goals. This typically included acquiring land or properties needed to achieve a strategic objective. It could be farmland needed for road widening or a building next to an at-grade car park that was needed to expand the car park. These were always justifiable expenditures; they were just not usually in the approved capital works program. The amount of money required was impossible to predict in any year but some was always required.

Each of the categories had unwritten guiding principles for capital allocation, and there was some predictability regarding the amount of capital required.

What can a capital allocation policy do?

At this point in my story, you may be asking why a policy was required. I have always sought council policy guidance on matters where they ultimately have to make decisions. Better to know what they think beforehand. Waiting each year for the council to decide on the capital works program it wanted to approve created uncertainty and prevented investment in the capability to deliver a capital works program reliably. The pattern of decision making I uncovered suggested there were already ‘unwritten rules’ determining how capital was allocated.

Formalising the 'unwritten rules' and getting them approved provides certainty. It not only helps improve capability to deliver capital works projects, it also helps with long-term financial planning and ensures assets are properly funded. The council doesn't have to follow the policy but any departure can be evaluated to understand the ramifications for delivery, funding and asset performance.

The policy helps councillors by putting them in the driver's seat for capital allocation. It enables the Council to proactively direct capital investment decision instead of reacting to the set of projects the CEO proposes each year. The broad direction set by the Council can focus organisational effort in proposing a capital works program to optimise expenditure on the 'highest and best' use of funds available in each category or providing advice when more or less money should be spent on each category. There is the potential for a policy to create efficiency in delivering the Councils outcomes.

The community benefits when the council's capital investment plans are clear and consistently delivered. They know what the limits are that the councillors are working within, and what to expect each year. If they want to influence the Council's decision on capital allocation, they know where to focus their effort and what they need to do to achieve a change in policy. It would also be useful to improve community knowledge of the reasons for taking on debt to implement capital projects or making applications for a higher rate cap.

A capital allocation policy demonstrates responsible stewardship of community assets and public infrastructure by the Council and the organisation. It aligns political and managerial accountabilities and helps address the fundamental conflicts involved in approving an affordable and deliverable capital works program. A capital works program that might be affordable but was unachievable only wastes resources and disappoints everyone.

What are the benefits of a capital allocation policy?

I have highlighted some of the key benefits below from the perspective of the community providing the funds, councillors making the decisions, and the CEO responsible for delivering the capital program.

If you read the example policy below, you will see there are other benefits within the organisation as capital allocations, funding sources and business cases are aligned to support project selection.

The community can benefit from better services if the assets required to deliver them are available when they are required, a more likely outcome when service planners can see future capital allocations.

A capital allocation policy can introduce transparency into decision making for all councillors, the organisation and the community.

A policy can help to align political and managerial accountabilities to achieve better outcomes for the community.

A policy can enable the organisation to invest in capital works delivery capability knowing it will be required. and the CEO can then be held responsible for delivering the capital works program.

Capability development can be focused on the largest or highest risk categories of projects when they have been identified.

Expenditure can be linked to funding sources and arguments for debt or rate cap increases can be made with evidence of both demand and capability to deliver.

What are the lessons?

There were several lessons. Here goes.

Introducing a policy into a ‘policy-free zone’ is not always welcome. It effectively shifts the power in decision making from the organisation to the council when instead of reacting to officer bids the council is proactive in directing the organisation on the funding it will provide for each category of capital works. Obviously, settling on this allocation needs to be a collaborative process, however, once it is done it requires officers to find the highest and best use for those funds when nominating projects in each category

Within the organisation, a policy can be seen as a constraint by those accustomed to winning the annual capital works bidding ‘chook raffle’ (as it was recently described to me be an experienced executive). A capital allocation policy evens out the playing field for those categories of capital expenditure that rely on arguments for funding based on asset condition, not community demand. It is a simple fact that there are less senior officers managing assets than there are managing services, and as someone once said to me, “people vote and assets don’t”.

A capital allocation policy highlights the gaps in service planning. It is impossible to confidently allocate capital in the future to asset upgrade and expansion, or new assets, without some prediction of the demand for services and the assets required to deliver them. Current council service planning processes are ineffective and a senior executive recently said to me that they think is has failed. It is slow and unresponsive, reinforces the status quo, and doesn’t anticipate demand well or effectively weave what understanding of demand exists into the capital works planning.

A capital allocation policy, especially one like the example below, is a complicated document. It covers a lot of organisational territory. To be successful, it needs changes in thinking and behaviour across the organisation and councils struggle with such organisation-wide change.

Example of a Capital Allocation Policy

Background

The current approach to capital allocation treats all capital works in the same way for the purposes of capital planning, business case development and governance. While this has created consistency, it is not fit for purpose in all cases. It can be improved with clear direction on the current priorities for the use of available capital.

This policy proposes a revised approach to capital planning based on different streams of capital investment and different sources of funds.

There are five major streams of capital investment by Council:

1. Asset Renewal (as per the Asset Plan).

2. Asset upgrades and creation (driven by service plans).

3. External commitments (e.g. Developer Contribution Plans).

4. Investment in the organisation ( to improve productivity or provide a financial return).

5. Strategic projects (ideas driven by economic opportunity, e.g. acquisition of land or property).

Categorised capital allocation

The table below provides an example of categorised capital allocation showing the proposed share of available funds allocated to each category and the sources of funding.

More detail about each of these categories is contained in Appendix 1.

The amount allocated for renewal of existing assets should reflect the annual depreciation and service and asset strategies and plans. It has historically been around 50% of Council’s budgeted capital expenditure and this is consistent with VAGO sustainability indicators to avoid an asset replacement gap.

The amount for external commitments is dependent on obligations created through contracts or Developer Contribution Plans (DCPs) and Council must meet its commitments as they fall due. The amount (and the percentage of available funds) will vary from year to year, as will the split between Developer Contributions (DCs) and rates (newer DCPs require less contribution from Council).

The other budget allocations need to reflect the objectives of Council-adopted strategies and plans.

The role of the Executive Management Team (EMT)

The EMT firstly identifies the available funding source or sources for each stream and sets the percentage of the annual budget to be allocated to each stream. The Long-term Financial Plan will identify the funds available each year, which will be apportioned according to the percentages determined by EMT. This is a one-off process that will set the amounts in the draft capital budget and should be reviewed every 3 years.

Then within each stream, EMT will conduct a Capital Works Initiation Review and agree as a group, based on direction from Council, which priority projects they intend to progress within each stream, before business cases are developed. This needs to happen in October each year. The annual business case development and evaluation process will then focus on the planning and deliverability of the priority projects identified by EMT.

Where there is expected to be sufficient funds, the EMT will also ask officers to prepare bids for the balance of funds not pre-allocated by EMT to come up with highest and best use. The PMO will facilitate the process in line with the Project Management Framework.

The business case template and the Capital Evaluation process will be adjusted to reflect this new approach. The annual list of capital works projects capable of delivery will be complete by February.

New steps in capital allocation

This approach will require EMT to collectively consider projects at the initiation phase, before investing officer time into the development and evaluation of detailed business cases and project management plans. EMT’s focus will be “How much should we invest, and into which projects/areas?”

The Capital Evaluation process and the Project Initiation and Business Case templates will be reviewed to support the evaluation required to make decisions about which projects should be done, and whether the Council is ready to deliver those projects. The Capital Evaluations focus will be “Can/should we deliver this now and how will we do it?”

Appendix 1 – Capital investment category description

1. Asset Renewal

Examples

Road reconstruction

Road resurfacing

Building asset renewal

Renewal of sporting surfaces

Fleet replacement

Library collection replacement

Playground renewal

Sponsor

These projects are generally sponsored by the Director Technical Services.

Funding source

These works are funded primarily by rates revenue.

Factors which drive planning

Asset management plans based on condition audits provide an evidence base for the renewal of assets over their lifespan. Fitness for purpose assessments and service strategies determine whether assets are renewed, upgraded or removed.

Renewal projects mostly exist in rolling programs. Each needs an evidence base (i.e. Service and Asset Plan) which is reviewed periodically, in line with Council term.

A four-year plan and funding allocation can be made at start of Council term, based on condition audits and Asset management plans. Relevant teams can manage to this budget, shifting timing etc. to get the most efficient and high-quality outcomes.

This work can be planned or responsive in line with activities in other categories. For example, where there is an upgrade of a facility, prioritise renewal of assets at that site at the same time.

Business case

A business case is not required if a Council-adopted Service & Asset Plan exists (or Ten Year Asset Plan).

Ongoing costs

Consideration should be given to when renewal results in a change to asset performance (ongoing utilities or maintenance costs, or specialist skills of operational staff).

Opportunities for improvement

Analyse asset management plans and their links to Service Plans in the context of existing and emerging community needs.

Develop plans for asset classes and major facilities, such as IT equipment, sporting facilities, sporting surfaces and floodlighting .

Review the Service Plans which inform asset management plans.

2. External Commitments (inc. DCP projects)

Examples

New community centres;

New sporting fields;

New sporting pavilions;

Some new roads and intersections.

Note that developers usually deliver passive open space and local roads in these growth areas and the assets are gifted to Council.

Sponsors

These projects are generally sponsored by Director Community Services.

Funding source

Developer contributions provide the majority of funding for these projects. In addition, projects may be eligible for grants. In the absence of grants, Council “tops up” the difference between the developer contribution amounts prescribed in the Developer Contribution Plans and the actual cost. All cost escalations over time or risk in cost under-estimates is with Council.

The current mix of funding for DCP projects varies, depending on standards expected for each type of infrastructure, and depending on the Developer Contribution Plans (not all DCPs provide similar proportions).

Factors which drive planning

The inclusion of infrastructure in a DCP determines the base-level of facility to be provided. Additional service planning within Council determines the specific requirements for each project.

Adopted policies such as the Sports Strategy and the Community Facilities Strategy prescribe some standards for growth infrastructure funded through DCPs.

Business case

The focus of the business case should not be whether this is a good project because the need for the project has been determined by the approved PSP. Instead, the focus should be on whether it is ready or able to proceed at this time, and whether the additional investment (or top-up) is justified

Ongoing costs

More work needed on the costing model for:

Utilities

Whole of life cost (i.e. cleaning, maintenance and renewal)

Operational staff (service staff and facility management)

Whole of life asset and operating costs need to directly feed into budget planning for Facilities and Open Space and Roads and Maintenance.

Opportunities for improvement

Review standard of delivery of community centres, pavilions, sporting surfaces and roads

Review timing of delivery of community centres, pavilions, sporting surfaces and road

3. Asset Upgrade and Creation

Examples

Pavilion upgrades

Road duplication

New library

New sportsfield

Sponsors

Driven by service need, therefore usually Director Community Services

Funding source

These works are currently funded primarily by rates revenue. Some may attract grants from state government and other partners.

Factors which drive planning

Service Plans linked to asset management plans should identify what is needed. This may be considered a “wish list”, subject to annual funding capacity, grants availability and political will.

Service areas should maintain and prioritise this list ongoing in consultation with PMO, and EMT and Council can consider introducing new projects where there is capacity at quarterly reviews.

Also consider funding design ongoing so that “shovel ready” projects can be prepared and activated quickly when grants or council funding becomes available.

This is the category with the most capacity for discretion in decision-making, and where Councillor-driven projects are most likely to sit.

Business case

Business cases are submitted annually. Evaluated for evidence of meeting a service need, triple bottom line outcomes, and readiness.

Ongoing costs

More work needed on whole of life costing model for:

Utilities

Maintenance

Renewal

Operational staff

This needs to directly feed into budget planning for relevant operational areas.

Opportunities to improve

Review Service Plans and strategies which inform the assets required.

4. Investment in the Organisation

Examples

Gym equipment upgrades

ERP project

GIS upgrade

Solar panels

Sponsors

It depends on the part of the organisation.

Funding source

These works are currently funded primarily by rates revenue. It makes more sense to borrow to fund projects which provide a financial return through increased productivity or revenue.

Factors which drive planning

Return on investment analyses should drive these investments, showing the cost-benefit ratio of available options.

Capital investment should be planned at start of Council term and reviewed annually.

Business case

The business case will need to include a financial return on investment analysis, a requirement to measure benefits realisation, and a resourcing plan indicating if current personnel will implement, or additional fixed term roles are needed.

Ongoing costs

Must be included in business case and form part of the return on investment argument.

Hurdle rates should be set to guide business plan development.

Opportunities for improvement

Review productivity drivers and plans for organisational performance improvement

Review strategic plans for IT and environmental sustainability and update asset management plans in accordance with them

5. Strategic Projects

Examples

The Esplanade upgrade

Various vacant town centre sites

Heritage buildings

City Centre Streetscape Framework

Sponsors

Driven by CEO and EMT.

Funding source

These works are typically funded primarily by rates revenue. Some may leverage partnerships from state government and other major partners. It may be appropriate to consider borrowings to fund acquisitions.

Given the role of these projects in shaping the city’s future, there is an intergenerational equity argument for funding them entirely or partially from debt.

Factors which drive planning

Economic and urban design factors drive the planning. The timing can be outside of Council’s control if it is reliant on when landowners are ready to sell.

Business case

Business cases submitted annually. Evaluated for triple bottom line outcomes, ROI, and measures required to deliver in the required timeframes.

A custom business case template is to be used for property acquisition and brought to EMT and Council as opportunities arise.

Ongoing costs

More work needed on whole of life costing model for:

Utilities

Maintenance

Renewal

Operational staff

This needs to directly feed into budget planning for relevant operational areas.

Opportunities to improve

Review Community Plan to determine the future of the city

Leverage planned state government work

Note

I want to thank the former colleagues who helped develop the capital allocation policy or who reviewed early versions of this post.