2000 words

Image: Copilot

Working with a community advisory group

In local government we often need to work with community groups to learn and gain insights into the needs and expectations of the community. This story starts with a group established to advise on public open spaces.

9.00 am on Wednesday, 8 June 2005

The next meeting of the Advisory Group is scheduled for 8.00 tonight. The Chair, a councillor, drops by to discuss how we can keep the group 'on topic' at the meeting.

The Advisory Group is made up of residents with 'expertise or significant interest' in the trees and open spaces of the municipality. She is frustrated by the tendency of the group to focus on detailed operational matters rather than the big picture strategic issues it was established to advise on.

What can we do to help the group be more strategic in the meetings?

How can we help a group to be more strategic?

This was a real group and a real situation - one that I have experienced several times since then. The councillor’s concerns were valid. The quarterly meetings had become a reporting session on long grass, weeds in garden beds, and uncollected litter. In an urban open space network of over 600 hectares, it isn't hard to find examples where maintenance hasn’t been done or done properly. None of the issues being raised were a major failure in the service, but it was what group members noticed when they used open spaces. In the absence of any support or direction to do otherwise, they felt compelled to dutifully report them at the Advisory Group meetings.

And it wasn't as though there were no strategic issues to discuss. The Street Tree Strategy and Open Space Strategy were both due for review. The experts were having difficulty looking beyond obvious signs of something not being the way they thought it should be, to see the points of strategic leverage to improve open spaces. The connection between council strategies or policies and operations is often difficult to see.

I suggested to the Chair that we needed to elaborate on the context for the work of the group to help them focus on the more strategic advice that the Council needed and expected from them. She agreed. It was then an 'over to you' moment then for me to work out how.

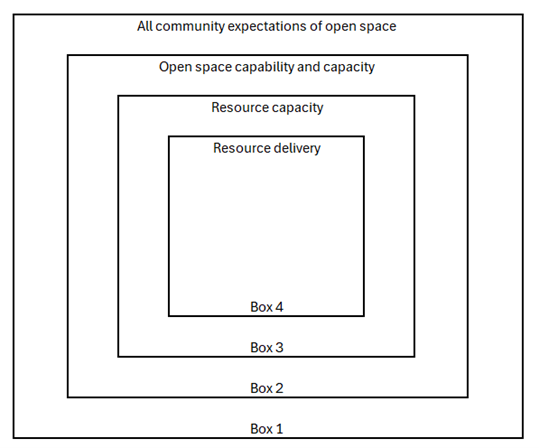

In a moment of clarity, I drew a set of concentric boxes.

The first and largest box represented the sum of all the things that each resident wants the Council to provide in open spaces.

The second and slightly smaller box represented what the open spaces are capable of providing.

The third and even smaller box represented the resources the Council has available to provide open spaces.

The fourth and last box sat inside this box and represented what has been achieved with the available resources in open spaces.

The set of concentric boxes from the whiteboard.

I knew that abstract conceptual ideas are often difficult for people to understand. In this case, the councilor understood it and thought it made sense and would work with the Advisory Group. We decided to give it a whirl that evening and challenge the group to say which gaps they thought they should be focusing on.

The advisory group meeting

8.00 pm on Wednesday 8 June 2005

I wheeled a mobile whiteboard into the meeting room. I then proceed to draw the set of concentric boxes I had drawn for the councillor.

I explained that we know community members have a range of expectations of their open spaces (Box 1). We also know that the existing open space network is only capable of providing for a range of activities, and that its capacity to accommodate some of those activities is limited (i.e. all community expectations can’t be met) (Box 2). The resources available for open spaces are limited (Box 3) and the use of those resources is not without losses and waste (Box 4). In an ideal world, there would be no gaps between the boxes.

The group was attentive and interested. The members working in professional jobs understood the importance of context in providing advice. Overall, the response was encouraging and the members immediately started discussing which gaps they thought they should work on.

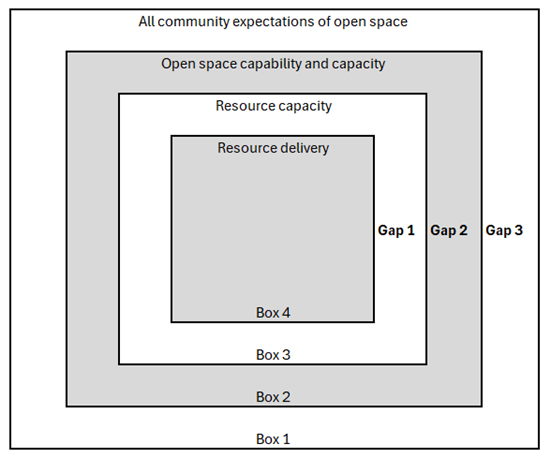

The result was unsurprising for a group of intelligent people. They immediately decided that Gap 1 between the resource capacity (i.e. resources available) and what those resources deliver is the responsibility of council officers to close. The gap between what open spaces are capable of providing and the resources necessary to optimise it (Gap 2) was of interest to the group, but they realised it could only be closed at budget time. They asked for an extra 'budget meeting' to be scheduled each year so that they could understand what was being funded and provide their advice.

The gaps identified by the Advisory Group.

The gap that they selected for their work was between the sum of community expectations of open spaces and what the existing open spaces are capable of providing (Gap 3). They saw advising on this gap as the best use of their time and most influential because it could help the Council understand how to optimise the investment in management and development of open spaces.

This is the gap where Council policies, plans and strategies are critical. They influence decisions to allocate resources, which then determine the capability and capacity of the open spaces to meet community needs and expectations. Working on this gap then flows across into Gap 2 and the operating and capital resources made available for open spaces. At last, the Advisory Group had a clear understanding of what they wanted to do.

This change in thinking was a breakthrough for the group and for me. Here was a useful tool to assist group thinking and help communicate some difficult concepts in providing public services, which had so far evaded us. The councillor was particularly impressed. Not only would it make the group more functional and effective, but it would help her to communicate with her colleagues on the Council about the group's work. She would also be able to explain to other community members how the group worked to represent them.

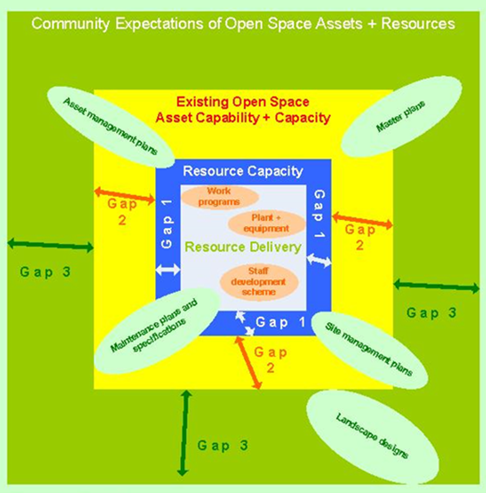

We used the final version of the diagram that went out with the meeting minutes regularly to remind ourselves of the choice to focus on Gap 3 and be strategic. The diagram is shown below.

The diagram provided to Advisory group members in the meeting minutes (Credit_ Christopher Deakin)

Moving from open space management to public value

My success in using the set of boxes to help explain some difficult concepts regarding open space to the Advisory Group and the councilor led me to examine how I could adapt the thinking for other activities. I realised that some of the specific references to open spaces could be generalised. This thinking was informed by my reading about public value, an idea that was topical in local government at the time.

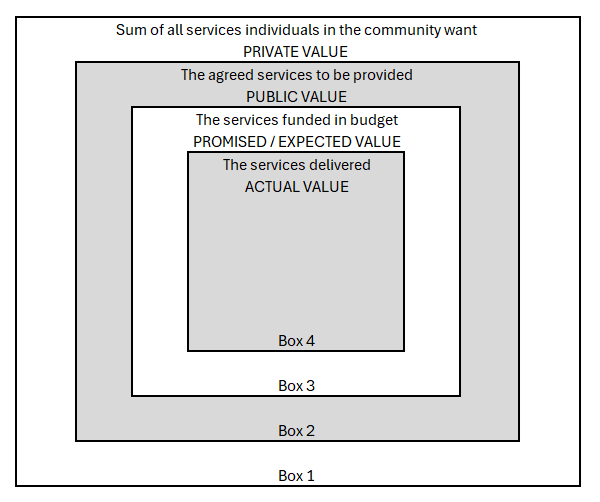

Value boxes

Box 1 is really the sum of all expectations of private value held by the members of the community (i.e. the total of what each person would want the council to do and evidenced by the individual service requests made of the council). Box 2 is the public value agreed by the community (i.e. what is agreed by the community to be valuable to do with their collective resources and evidenced by council policy, strategies and plans). Box 3 is the amount of resources the council is able to allocate to implement those policies, strategies and plans in any given year (i.e. the annual budget). Finally, Box 4 is what actually gets done using those resources (i.e. the services delivered in accordance with the budget and council policies, strategies and plans).

This is shown in the diagram below. I have used it regularly to contextualise problems when working with new team members. It has been a powerful communication and clarification tool to ensure we are putting our effort where we need to for the gaps to close or disappear.

The Nested Value Boxes

Example: Street trees and Nested Value Boxes

An example of the application of Nested Value Boxes is management of street trees. Many residents take an interest in the tree planted in the street outside their house. They have preferences for the type of tree and how it is managed. Some want the tree to fit in with their home garden, and some don’t want a tree at all. This is private value related to the individual interests of the resident. Most councils have a Street Tree Policy that seeks to achieve goals in the public interest for the whole community. This has been created through a process of community engagement and adopted formally by the elected Council. This represents the agreed public value.

Reconciling private and public benefits of street trees

As anyone who has dealt with street trees will know, reconciling private and public value benefits can be challenging. I once had to resolve a situation where 50% of the people living in a street petitioned the council to remove the street trees, and at the next meeting the other 50% petitioned the Council to retain them. At the street meeting, both groups said they should get what they want because they pay their rates. The Council policy was clear - street trees were planted for whole of street, suburb and city benefits, and could not be removed unless they were dangerous or a serious nuisance. Neither applied in this case. I was able to resolve the conflict using the value boxes.

Budgetary provision for street trees and public value

The annual budget is usually allocated for a defined range of services to be provided. In the case of street trees, it will be for new trees to be planted, old trees to be removed, and the rest of the trees to be inspected and maintained. This creates expectations of value. When costs go up, or storms require staff to leave routine maintenance works, and programs cannot be completed, people in the community rightly get upset because their expectation has not been met. Something didn’t happen to the tree outside their house, or the trees in their street, that they had been told would happen. The actual value is less than the expected value.

Using the concept of value with council officers

I have also found the focus on creating different types of value to be useful working with teams of officers. The community is totally focused on their idea of value in what they expect from the council, whether it is a private or public value expectation. In comparison, council officers tend to be focused on what services cost and managing expected and actual value. How often have you heard a council officer say, ‘if we give them what they want, everyone else will expect it and we will blow the budget’?

The lesson of 4 decades of leadership roles in councils is that a solitary focus on cost never works in public services and it only serves to create community dissatisfaction and then to drive costs up. I will write more about this in another post.

Finally, three uses for Nested Value Boxes

1. To assist communication between elected representatives, the community, and officers in determining whether a matter is operational or strategic in nature. It can help avoid the breakdowns that have led to monitors and administrators being appointed to councils by the State government. For example, deciding how to respond to demands for private and public value, and closing this gap, is fairly and squarely the domain of elected representatives.

2. It is also useful for individuals and organisations in the community to help them understand where their concerns lie and how to get the attention of the council and have them resolved. It can help focus the conversation. For example, failure to deliver promised or expected value is the responsibility of officers working under Council direction, and a different conversation to one where a service of private value has not been agreed to be provided.

3. Finally, it is useful in discussions between officers on the type of value the council provides, where responsibility lies for each type of value, and how decisions are made for each. For example, closing Gaps 3 and 2 are the responsibility of elected representatives with support from officers, especially Gap 2. In comparison, closing Gap 1 is the responsibility of officers, who are accountable for running effective and efficient operations.