Introduction

Many years ago, I was trying to work out how urban landscapes rich in natural values could be presented in ways that met community expectations. I had successfully asked my council to fence and protect some remnant legless lizard habitat in parkland, only to have the Councillor who moved the motion request that now we were fencing the area, could we remove all of the rocks and irrigate it so that it would look nice. It seemed to me that people don't mind nature if it is tidy.

Cues to care

"Ecological quality tender to look messy, and this poses problems for those who imagine and construct new landscapes to enhance ecological quality."

Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames (1995)

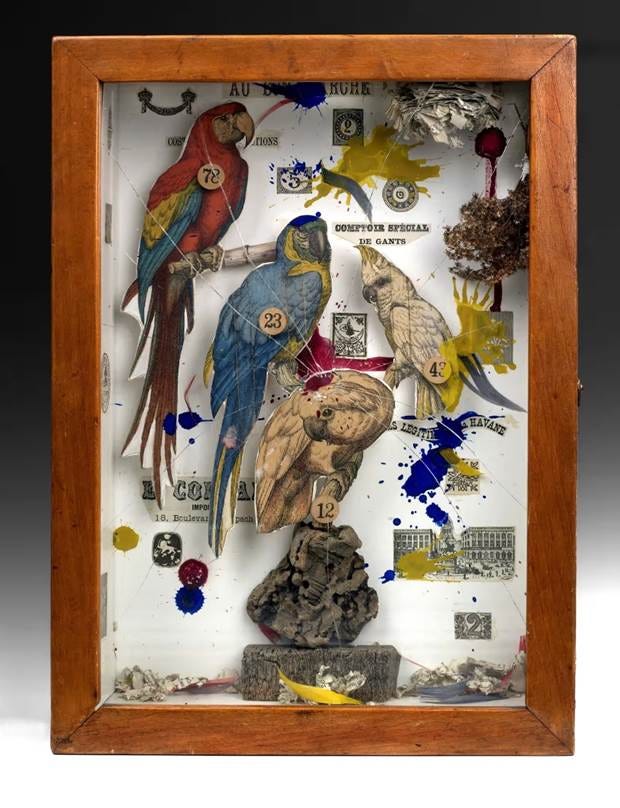

I heard about the work of Professor Joan Nassauer when she was the keynote speaker at the 'Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames' conference in Melbourne. Nassauer talked about 'cues to care', which place the unfamiliar or undesirable within the familiar and attractive. She compares her theory to the assemblage art of Joseph Cornell who placed seemingly random objects in carefully presented boxes.

Habitat Group for a Shooting Gallery, Joseph Cornell, 1943. Photograph: Mark Gulezian

I had practiced using cues to care (more about this at the end of the story) and these experiences led me to write a story that was published on the Urban Landscape Management website in 2017. They have generously agreed that I can republish it here. I have written the story in the Michelle Bowden persuasive style.

Here is my story.

How can using ‘cues to care’ enable you to meet people’s expectations about public landscape appearance while using fewer resources?

“The landscape of any farm is the owner’s portrait of himself”.

So wrote Aldo Leopold in 1939 and in doing so he connected the social identification of a landowner with the appearance of their land. Our landscapes are public portraits of ourselves. A neat and tidy garden is a sign of effort, pride and neighbourliness.

Similarly, people have preferences for the appearance of urban public landscapes. Often, these preferences are driven by the desire for deliberate intent to be evident in the landscape. It is important for managers to understand these preferences and to control the appearance of landscapes to provide appealing aesthetic experiences. An approach is needed to match the desire for neatness in urban landscapes with the inherent messiness of vegetation. Using cues to human care is an approach that will help you to conserve resources and meet people’s preferences for landscape appearance.

In this story, I will explain how using ‘cues to care’ can reduce criticism of standards of care, accommodate the inherent dynamism of landscapes, and improve resource efficiency. Changing the appearance of landscapes can be threatening for some people and disappointing if the change is not what they expected. This creates a challenge for managers. Many urban landscapes already do not meet community expectations for care and presentation. ‘Cues to care’ provides a planned approach that will overcome concerns about change because it is based on our understanding of human psychology.

The use of ‘cues to care’ is discussed as a resource optimisation strategy in urban landscape management. This will overlap some aspects of the original use of ‘cues to care’ for ecological protection. There will be links for further information.

The term ‘cues to care’ was first used in 1995 by Professor Joan Nassauer in her article ‘Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames. She used the term to describe our cultural need to display care in landscapes. The idea is for the unfamiliar or undesirable to be placed within the familiar and attractive. The underlying motivation is the belief that landscapes that people enjoy are more likely to be culturally sustainable. ‘Cues to care’ was originally defined as cues that indicate human intentions in ecological landscapes in cities. I am proposing that ‘cues to care’ can also be thoughtfully used to signal human intention in the management and care of all urban public landscapes as a way to conserve maintenance resources.

Because ‘cues to care’ make the unfamiliar appear more familiar and comfortable, they are useful for managing landscapes that look different to the way people expect. This is particularly relevant to naturalistic landscapes, such as remnant grasslands, prairie and heath land. Cues are likely to vary from place to place and community to community.

So, what are ‘cues to care’? Some cues relevant to urban public landscapes include:

Removing rubbish, litter and debris. Cleaning up shows management presence.

Mowing a neat strip around an area that remains unmown. People might expect more of the area to be mown but they can see maintenance has occurred and the area has not been forgotten or neglected.

An associated idea is differential mowing where grass is cut to different heights or on different cycles. It is important to ensure that ‘patterns’ are clearly visible in the mown and unmown areas that make sense to a viewer. Follow contours or run parallel to fence lines or garden beds to create strong patterns with clean edges.

Use plants that are commonly cultivated. People are more likely to find the whole area more attractive if they recognise some of the plants as ornamental. Some contemporary groundcover plants are highly functional but indiscernible from weeds by the general public.

Provide fences on boundaries to establish ownership. Consider placing furniture in the area as a sign of human occupation. The landscape needs to look as though someone cares about it.

Put signs with information about the place. Explain how it is being maintained. People might not agree but they will know the area is intended to look the way it does.

How can you implement ‘cues to care’?

Lawn mowing is a resource intensive horticultural practice in many landscapes. Large areas of lawns are regularly mown. By mowing less areas or mowing less often, fuel energy consumption, air pollution and noise will be reduced. In addition, more grasses will flower and set seed, enriching ecological processes. With care, differential mowing can create attractively patterned, interesting landscapes. Operationally, mowing practice will need to be reviewed and mowing areas mapped, marked on site for operator convenience and schedules changed to mow particular areas at particular times.

Reducing resource use by planning maintenance as a series of interventions in response to changes in vegetation condition will make management of the landscape more environmentally sustainable. Routine maintenance scheduled for the same date each month or performed regardless of the actual conditions will consume more resources. It can also reduce biodiversity and impair ecological processes. Continually removing biomass by mowing will prevent flowering and seed set, and applying selective herbicides to create monocultures of grass reduces species diversity. Similar thinking can be applied to garden or flower beds. Use perennial or self-regenerating plants in ways that provide acceptable appearance throughout the year. Using ‘cues to care’ will ensure that cultural sustainability is not sacrificed in pursuit of environmental sustainability.

In summary, not every urban landscape looks the way people expect or prefer. ‘Cues to care’ provides a way to meet aesthetic conventions and be more environmentally sustainable. ‘Cues to care’ meet the cultural need for deliberate intent to be evident in the landscape. Cues are signs that a place is not neglected, even if it has been maintained the way you expect. Use ‘cues to care’ in your landscapes and be more environmentally sustainable.

If you don’t use ‘cues to care’, the resource intensity of your landscape maintenance will be greater. ‘Cues to care’ is a contemporary approach to landscape maintenance that provides an opportunity to match aesthetic preferences and expectations while reducing the amount of resources required.

Practising with cues to care

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, practices like differential mowing (i.e. mowing some sections of a park and not mowing others, or mowing some sections at different heights and frequencies) were being talked about in the UK as a way to save money. It had benefits for nature too, because grasses and herbs can get to seed if mown less often.

I remember sowing Fescue in the median strip of a very busy road and then only mowing a 1m wide strip down either side next to the kerb. This saved a lot of money for traffic control and mowing. I asked various people what they thought about the appearance of the median. Someone said it wasn't what they would do but it looked maintained and wasn't neglected. It was a sign of care.

Fencing natural areas was also commonplace, usually to exclude people and rabbits to protect vegetation. Nassauer explained how it could also increase community support for conservation. I tried this with success in a popular coastal area where I fenced the revegetated garden beds in high use areas with conservation-type fencing. The Conservation Team thought it was misplaced effort and a waste of resources. They wanted to fence worthier vegetation remnants.

In the end the fencing was popular (especially with the CEO and Councillors who regularly went to the beach area but seldom went to conservation parks) and the fencing budget was increased, which allowed fencing of other, worthier, areas.

Are there some lessons from using cues to care?

If you think carefully about what the community expects to see in their parks and public landscapes, there will be cues to the activities they value in presenting parks. The knowledge that natural areas are being managed is important in Australia because of the seasonal threat of grass or bushfire and the presence of snakes. If people think an area is neglected or out of control, they will call attention to it and resources will be required to respond to their concerns.

Mowing is one of the most resource intensive park maintenance activities. Reducing the frequency of mowing for large sections of park will reduce the annual cost of maintenance and reduce environmental impacts on biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions. There is a minimum number of times grass should be cut (I have seen calculations showing it is 7 times a year) before the resource intensity switches - i.e. you cut less often but it takes longer, uses more fuel, and costs more.

I suggest experimenting with changes to mowing and testing it with your team and your community. It is worth a go.

References

Professor Joan Nassauer article ‘Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames’

Urban Landscape Management - an online resource for open space managers