2800 words

Credit: Copilot

Hard rubbish time used to be a free for all with everyone going through the streets to see what treasures they could find. It was the occasion twice a year when going for a walk in your neighbourhood could turn into a sort of retail adventure. I once helped a daughter living in a share house carry home some ‘good chairs’ and then to put the old ones out for the collection. She was delighted with the upgrade.

Then times changed.

Residents started complaining about the mess in streets. The Safety Regulator issued guidance on how to reduce hazards from hard rubbish awaiting collection. Residents started reporting disturbance from midnight scrounging and fights over furniture. I had to investigate a report of a woman on her way to the horse races in her finery who stopped to wrestle another woman over an antique table. The environmentalists in the community were starting to question what was happening to the materials being collected. It was all being crushed in a compactor truck. They wanted to know how much was being recycled?

It was time to act.

Introduction

I searched for a way to design a new service to replace the traditional hard waste collection and I discovered blueprinting. In short, blueprinting is a way to visually represent the key steps in a service process using a flow chart. It is a living document to be used after implementation to continue refining the service in response to user feedback. A key feature of blueprinting is identification of potential fail points where service can be disrupted, and the inclusion of recovery plans that make the service ‘safe-to-fail’. I knew this was an important service and change would impact every household in the city.

There are three lessons from using blueprinting at the end of the story for those who like to cut to the chase.

This story tells how I read 'Designing Services That Deliver, ' in the Harvard Business Review by G. Lynn Shostack (1984) and combined it with operations management theory I had learned during my MBA. I describe how the current service was examined and service operations were designed to achieve new service objectives from the customer viewpoint. Finally, the service we designed determined the type of operation required to deliver it.

Reviewing services

For several months the Waste Coordinator and I had been reviewing waste services. We had looked at weekly kerbside waste collections and were now moving on to the hard waste collection. We saw this service as valuable for households to dispose of waste that was unsuitable for inclusion in kerbside collections, especially if they could not easily transport their waste to the council’s transfer station.

Our council was active in environmental sustainability and willing to take a risk to improve. We were all set to make changes. This turned out to be a more difficult challenge than anyone expected.

How did the old service work for residents?

The hard waste collection service being offered was common to many councils at the time. Twice each year in November and May every resident was able to put their hard waste in the street outside their property for collection and disposal. There were some limits on the amount and type of waste that would be collected, and when and how it should be placed in the street, but these were often ignored.

Problems

This meant that for a 4-to-6-week period, streets throughout the municipality would be covered in waste awaiting collection. Unauthorised collectors would sort through the waste to take metals or other materials of value and often leave the remaining waste strewn across nature strips and footpaths. The authorised collectors paid by the council to collect the waste would then place all waste into a compactor truck, crush it, and take it to a transfer station where materials were recovered for recycling. Typically, this was only metals, timber, and cardboard, with the rest going to landfill.

What were the benefits?

This type of service supported informal reuse and repurposing when community members took waste from outside other people's houses. For many residents the Council collection dates set a deadline to clean up their property, especially the pre-Christmas one. Houses and gardens were cleaner and safer because you either cleaned up or missed out.

Safety concerns and hazard controls

Worksafe in Victoria issued a handbook on safe collection of hard waste in 2008, recommending hazard controls. These included requiring waste to be contained within residents' properties and councils providing education on types, sizes and placement of wastes. The handbook recommended that if waste had to be placed in the street, it should not be placed out before the nominated collection date and be collected within 5 days, and that councils should have an enforcement program to ensure compliance.

Impracticality

In practice, these recommendations were difficult to implement. Once residents saw waste being put out in one part of the municipality, they would put their rubbish out to make sure they didn’t miss out. Most rubbish was put out on a weekend within the collection period because it suited the resident, not on the day before collection was scheduled.

Collections could also take much longer than planned if a lot of waste was put out, and there was frequently a need to go back to areas that had already been collected when residents were late putting out their waste. These problems occurred every year.

Were there other complaints?

Apart from the public safety hazards, many residents complained that their street, and sometimes the whole municipality, looked like a tip for the months that collections were being made. Windblown litter could be a problem and sometimes hazardous materials, like asbestos, were put out for collection. Very little of the material collected was recovered and recycled. The cost of the service was unknown because it depended on the amount of material collected and how long the collections took to complete. The service often went over budget.

Response

In response to these problems, some councils had changed to offering a hard waste collection service on demand. Our team decided to have a look at whether that type of service would be better for our residents.

How could we design a new service?

Investigating other councils

A neighbouring council provided this type of hard waste service. Residents could call and book the collection of their waste when it suited them. We went to have a look and talked to them about how it was performing. They had been providing it for about 2 years and had made changes to the service design since it was introduced.

Their service provided residents with up to three collections for a specified range of wastes, which had to be placed in the front garden of the resident’s property. The collection would be made on the same day as the next scheduled kerbside bin collection.

When we visited, the council was struggling to make all collections on the next scheduled kerbside collection day because of the uneven numbers of bookings received for each day of the week. When this happened, the residents had waste in their garden for at least another week, potentially blocking the driveway and preventing them garaging their car. They also found that some residents didn't have space in their front garden, so they placed the waste in the street. This led to complaints from neighbours and the ‘dumping' of waste as neighbours added to the pile overnight.

Finding a better way

These examples of service problems highlighted that services don't always work the way you anticipate. I started looking for a way to plan a new service that would anticipate the things that could go wrong and have corrective actions already prepared. The plan would also provide a baseline for understanding the impact of any changes made to the service in response to residents.

How does service blueprinting work?

Combining the concept of service blueprinting with operations management offered a way to develop a workable plan that the team could make and use. The operations function is critical in a council because it produces the services which are a core reason for the council existing. Different types of operations have different characteristics that are important to understand for success, and the performance objectives of an operation are essential to understanding what matters to service users.

The service plan is shown in the illustration below. It compares the current service to the proposed service on 8 activities (central column) and compares the operations typology of the old and new service. It also lists the performance objectives of the new service and the objectives the team had in designing the new service.

The Hard Waste Service Plan

I integrated Shostack's blueprinting with operations management theory. The intention was to have a detailed plan for how the service would be delivered (the stuff that matters to customers) and to be clear on the type of operation we needed to set up (the behind-the-scenes stuff that matters to the council).

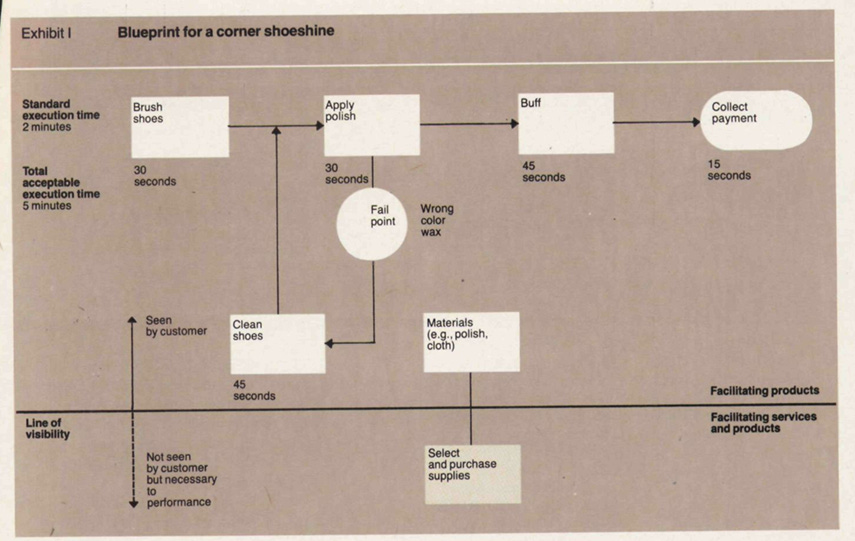

An example of blueprinting (below) is from Shostack’s article and shows the process to deliver a shoeshine service. It is much simpler than the hard waste blueprint but gives you a sense of what that blueprint covered. We started with the resident request and plotted each step through to payment of the contractor’s invoice. The times that mattered to us were how long each step would take in days to ensure commitments about collection dates could be fulfilled.

An example of a blueprint

This example shows how failure has been anticipated when applying polish (i.e. the wrong colour wax is applied) and a recovery loop has been designed into the service. The line of visibility separates thinking about parts of the service experienced by the customer from the ‘behind the scenes’ operations design required from the provider to make the service work.

The new waste service

The new service formed part of a suite of services. The service objectives were to enable residents to dispose of all wastes generated within their home and garden through a council service, being either a kerbside collections, booked hard waste collection, or by taking it to the transfer station.

This excluded demolition and construction wastes, which needed commercial disposal, and hazardous materials that needed to go into special collections held annually by the State government.

The design of the new service was informed by the team's knowledge of the type of wastes being generated by households that they were having difficulty disposing of. Either because they were unsuitable for kerbside collections, or they couldn't transport them to the transfer station. The type of rubbish being dumped arounf the city gave further insights into the waste our residents needed help with. Dumping is the ultimate sign that waste services have failed.

Performance objectives

The objective for the booked hard waste collection was that it would be convenient and flexible for residents to use, and it would facilitate better resource recovery. This led to the set of ranked service performance objectives from the customer perspective in the Hard Waste Service Plan:

1. Collecting the waste when we said we would.

2. Accepting a wide range of materials.

3. Not leaving waste behind.

Key design features of the service

From a council perspective, collecting waste in ways that protected the value of materials for recovery was also important. This led to some other service design features:

· The sorting of waste into 6 piles for collection’

· The use of 2 collection vehicles (a tray truck/van and a compactor).

In addition, appointing 3 contractors would give extra capacity in peak booking times.

State Government landfill licensing issues

The collection of sorted hard waste also gave the council access to multiple disposal sites, which started to reduce the growing risk associated with access to landfill. Not only had the government decided not to license any new landfills in the state, but the nearby landfills were also scheduled to close within a decade.

Budgetary control

Budgetary control was an important issue for the council, and the current arrangement where the cost was only known at the end of each collection period wasn't ideal. The amount of hard waste being collected was increasing each year and the budget was always overspent. The small amount of resource recovery and limited diversion from landfill (which was starting to be taxed more heavily) was adding to the cost.

Collecting from individual households, rather than clearing waste from the street, enabled control of costs and for the drivers of cost to be understood. We could identify the properties generating large amounts of hard waste and start talking to them about waste reduction.

Customer engagement

The operations typology was an important concept that informed the development of the blueprint. We understood from looking at our neighbour's booked hard waste service that we would be introducing much more customer interaction into the service. We would need to prepare for the customer calling to make the booking, help the resident understand how the collection would be made, and what waste would be taken. We also knew there would be more variety in waste collected and variation in demand for the service across the week and the year.

Variation in demand

Variation in demand was one of the most difficult aspects of the service to plan for. It is why the service was implemented with collection within 4 days rather than the collection day being tied to the scheduled kerbside collection day. It gave the team more work to do in batching collections to minimise time wasted travelling between properties, but the benefit was the ability to spread demand and make the collection on any of the 4 days. The reality was that some parts of the municipality made more hard waste bookings and having a single day to collect them would have created peak workloads and potential for failure. The 4 days enabled demand to be smoothed.

The team was determined that the service would be as simple as possible so that it was easier for residents to understand and there would be the least number of things that could go wrong. The service had to be reliable, and it had to be low cost. As it turns out these last two objectives saved the service from termination after a contentious council election.

Did the new service work?

I am always interested in whether people making big changes to services have ever tested whether they achieved what they set out to achieve. In this case, the change became a major election issue. Some councillors lost their seats because of the change. Others were elected on a platform of reverting back to the old service.

The change in service had been approved by the council and implemented the year before the council elections. I underestimated the fondness of residents for the old hard waste collections. The system had been in place for many years and was familiar. And, despite all the planning, we still had teething problems. There were examples that candidates running in the election could use to attack the sitting councillors on their decision to change. The local newspaper ran a series of negative headlines that fueled the debate. The lesson? - don't make changes to big services just before an election.

The newly elected council called for an independent review of the new service. This was challenging for the team and required the performance of the system to be analysed. Fortunately, the data was available to show that residents using the new system liked it, the recovery of resources was higher, and the costs were lower. The service remained in place and continues to perform well for the community.

“The review was very thorough and demonstrated clear achievement against the objectives of the new service, to the point where even those elected on a platform of returning to the previous hard waste model had to concede that it was a better service on all measures (Service Manager).”

My three lessons from blueprinting

1. Performance measurement. The blueprint provided a clear basis for assessment of performance. When introducing a new service, it is important to learn quickly and respond to feedback from residents by adjusting the service. The blueprint gives you a starting point and a baseline to measure whether the service is working. This proved to be the case in the independent review of the new service.

2. Transition. The blueprint helped set up the service for success. Predictable points of failure had recovery plans to minimise inconvenience to residents. A service can only really be designed to do things that you know will happen (i.e. they are predictable) but you know there will always be things you haven’t thought of (i.e. variation from what has been predicted), you need to be prepared to accommodate that variation.

3. Communication. The blueprint made communicating about the new service within the council (i.e. with executives, councillors and customer service officers) easier. While I know many people have trouble reading flow charts, it did provide something concrete to look at and explain. In the absence of a real-life example to show them, the team could talk through what was going to happen and who would be doing it.

References

‘Operations Management’ , 2nd Edition by Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers, Christine Harland, Alan Harrison and Robert Johnson(1998)

'Designing Services That Deliver, ' Harvard Business Review by G. Lynn Shostack (1984)

Both references are available online, although it will be a more recent edition of Operations Management.

Credit

Dr Karen Smith provided helpful advice and editing